Automated testing is a key part of software development toolkit and practice. fbp-spec is a testing framework especially designed for Flow-based Programming(FBP)/dataflow programming, which can be used with any FBP runtime.

For imperative or object-oriented code good frameworks are commonly available. For JavaScript, using for example Mocha with Chai assertions is pretty nice. These existing tools can be used with FBP also, as the runtime is implemented in a standard programming language. In fact we have used JavaScript (or CoffeeScript) with Mocha+Chai extensively to test NoFlo components and graphs. However the experience is less nice than it could be:

- A high degree of amount of setup code is needed to test FBP components

- Mental gymnastics when developing in FBP/dataflow, but testing with imperative code

- The most critical aspects like inputs and expectations can drown in setup code

- No integration with FBP tooling like the Flowhub visual programming IDE

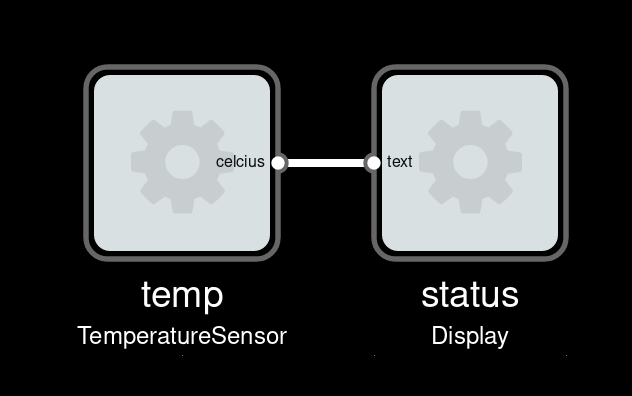

A simple FBP specification

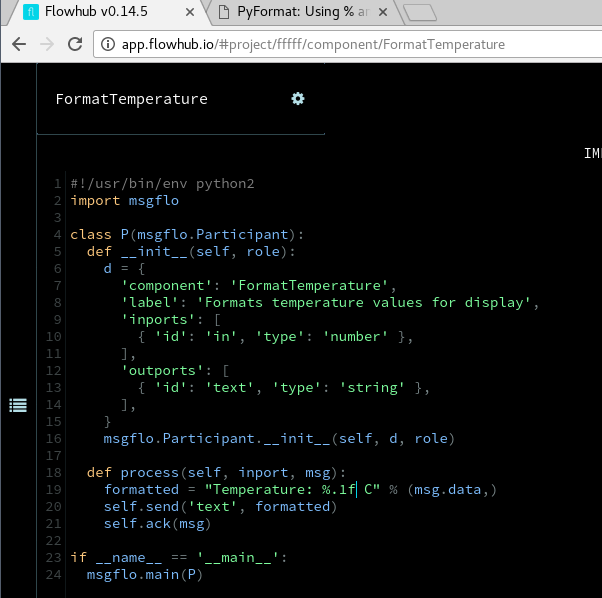

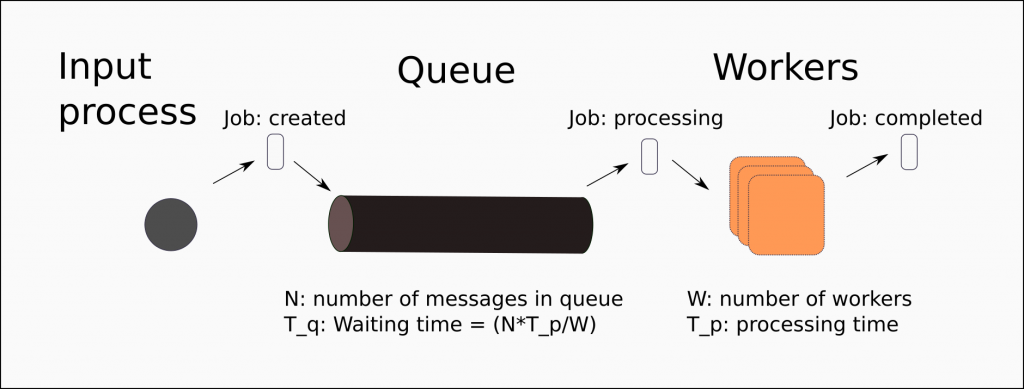

In FBP, code exists as a set of black-box components. Each component defines a set of inports which it receives data on, and a set of outports where data is emitted. Internal state, if any, should be observable through the data sent on outports.

A trivial FBP component

So the behavior of a component is defined by how data sent to input ports causes data to be emitted on output ports.

An fbp-spec is a set of testcases: Examples of input data along with the corresponding output data that is expected. It is stored as a machine-readable datastructure. To also make it nice to read/write also for humans, YAML is used as the preferred format.

topic: myproject/ToBoolean cases: - name: 'sending a boolean' assertion: 'should repeat the same' inputs: in: true expect: out: equals: true - name: 'sending a string' assertion: 'should convert to boolean' inputs: { in: 'true' } expect: { out: { equals: true } }

This kind of data-driven declaration of test-cases has the advantage that it is easy to see which things are covered – and which things are not. What about numbers? What about falsy cases? What about less obvious situations like passing { x: 3.0, y: 5.0 }?

And it would be similarly easy to add these cases in. Since unit-testing is example-based, it is critical to cover a diverse set of examples if one is to hope to catch the majority of bugs.

equals here is an assertion function. A limited set of functions are supported, including above/below, contains, and so on. And if the data output is a compound object, and possibly not all parts of the data are relevant to check, one can use a JSONPath to extract the relevant bits to run the assertion function against. There can also be multiple assertions against a single output.

topic: myproject/Parse cases: - name: 'sending a boolean' assertion: 'should repeat the same' inputs: in: '{ "json": { "number": 4.0, "boolean": true } }' expect: out: - { path: $.json.number, equals: 4.0 } - { path: $.json.boolean, type: boolean }

Stateful components

A FBP component should, when possible, be state-free and not care about message ordering. However it is completely legal, and often useful to have stateful components. To test such a component one can specify a sequence of multiple input packets, and a corresponding expected output sequence.

topic: myproject/Toggle cases: - name: 'sending two packets' assertion: 'should first go high, then low' inputs: - { in: 0 } - { in: 0 } expect: - out: { equals: true } inverted: { equals: false } - out: { equals: false } inverted: { equals: true }

This still assumes that the component sends one set of packet out per input packet in. And that we can express our verification with the limited set of assertion operators. What if we need to test more complex message sending patterns, like a component which drops every second packet (like a decimation filter)? Or what if we’d like to verify the side-effects of a component?

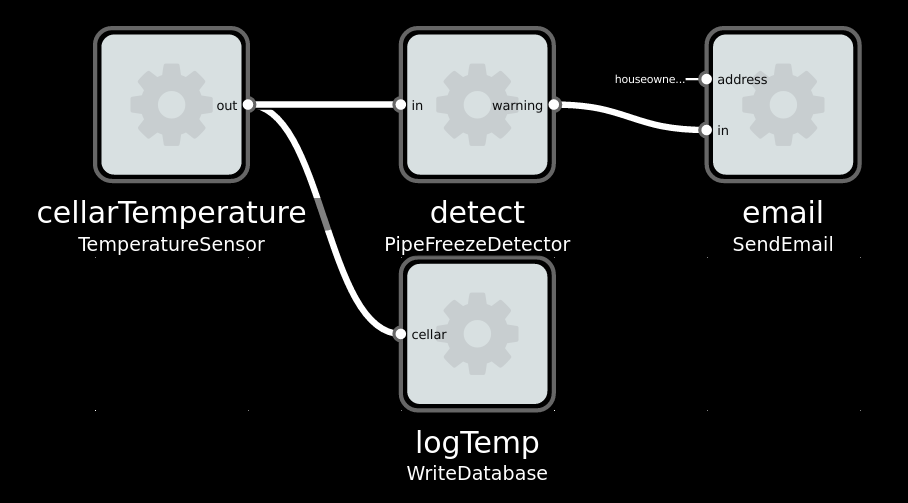

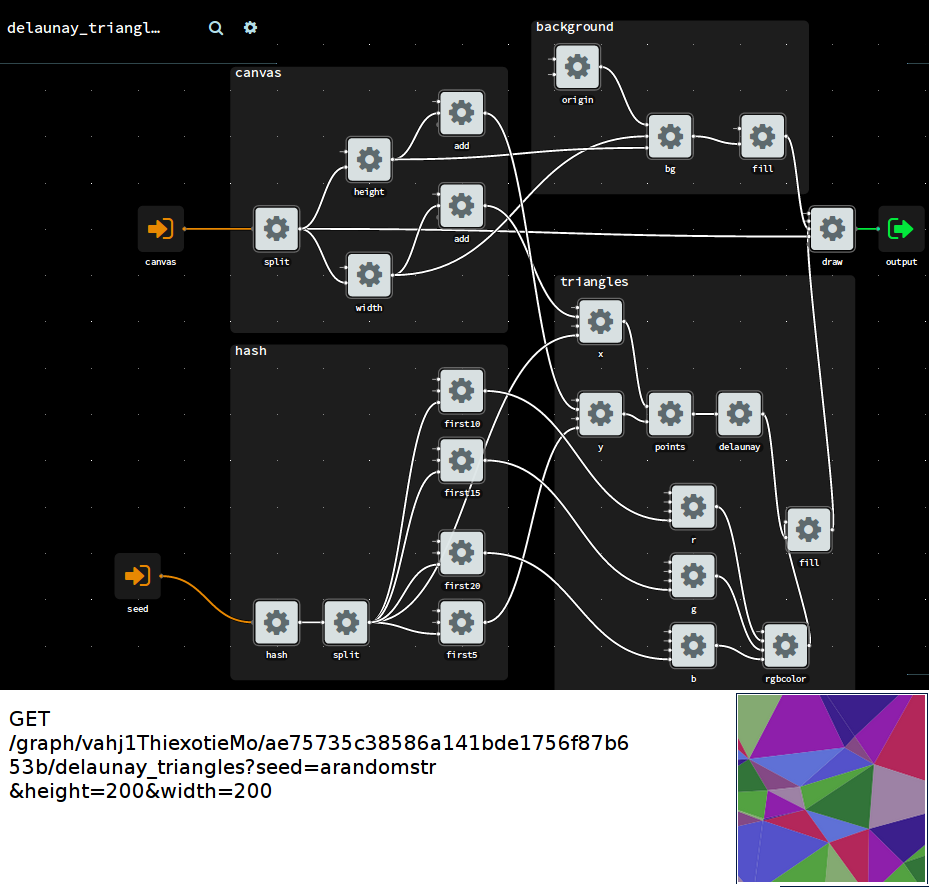

Fixtures using FBP graphs

The format of fbp-spec is deliberately simple, designed to support the most common axes-of-freedom in tests as declarative data. For complex assertions, complex input data generation, or component setup, one should use a FBP graph as a fixture.

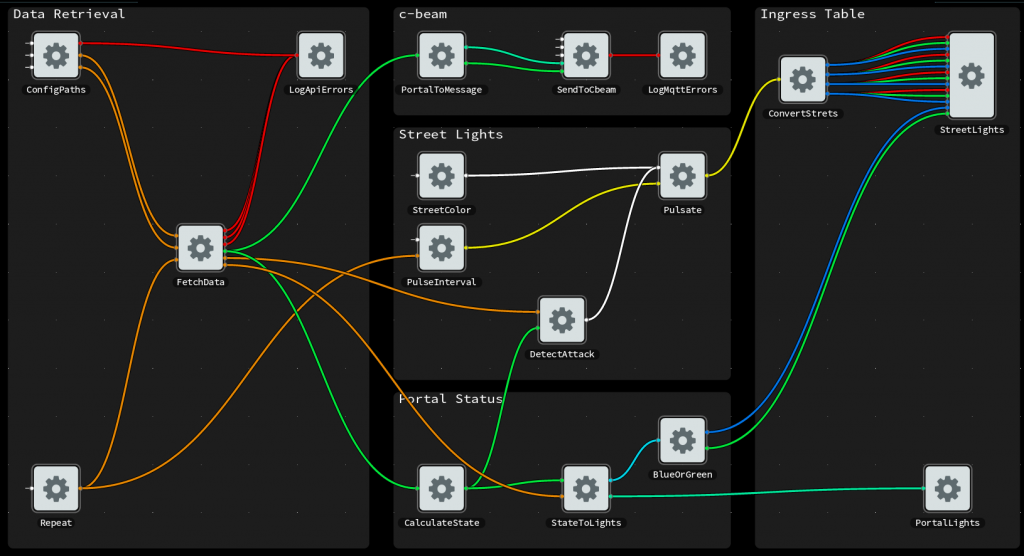

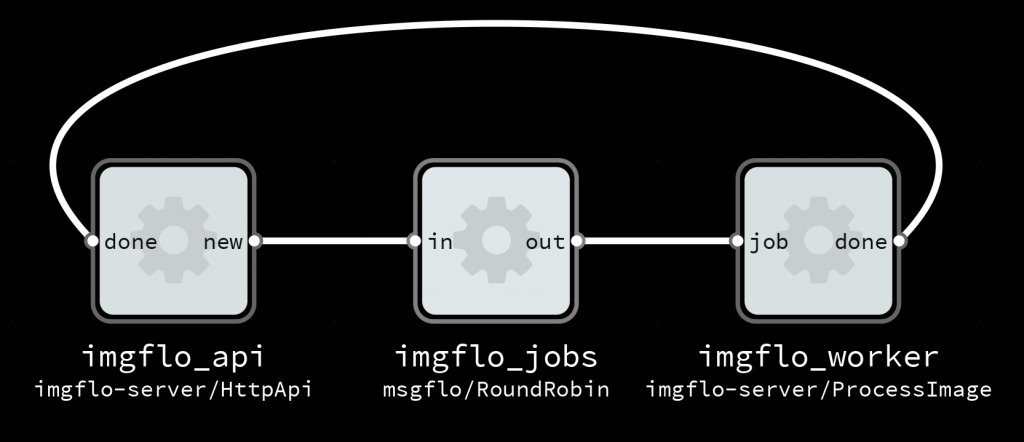

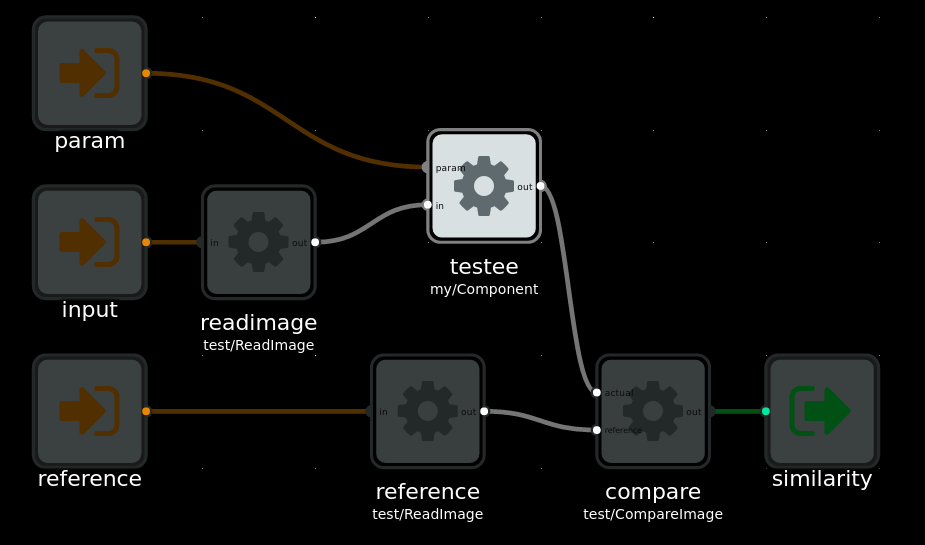

For instance if we wanted to test an image processing operation, we may have reference out and input files stored on disk. We can read these files with a set of components. And another component can calculate the similarity between the processed out, as a number that we can assert against in our testcases. The fixture graph could look like this:

Example fixture for testing image processing operation, as a FBP graph.

This can be stored using the .FBP DSL into the fbp-spec YAML file:

topic: my/Component fixture: type: 'fbp' data: | INPORT=readimage.IN:INPUT INPORT=testee.PARAM:PARAM INPORT=reference.IN:REFERENCE OUTPORT=compare.OUT:SIMILARITY readimage(test/ReatImage) OUT -> IN testee(my/Component) testee OUT -> ACTUAL compare(test/CompareImage) reference(test/ReadImage) OUT -> REFERENCE compare cases: - name: 'testing complex data with custom components fixture' assertion: 'should pass' inputs: input: someimage param: 100 reference: someimage-100-result expect: similarity: above: 0.99

Since FBP is a general purpose programming system, you can do arbitrarily complex things in such a fixture graph.

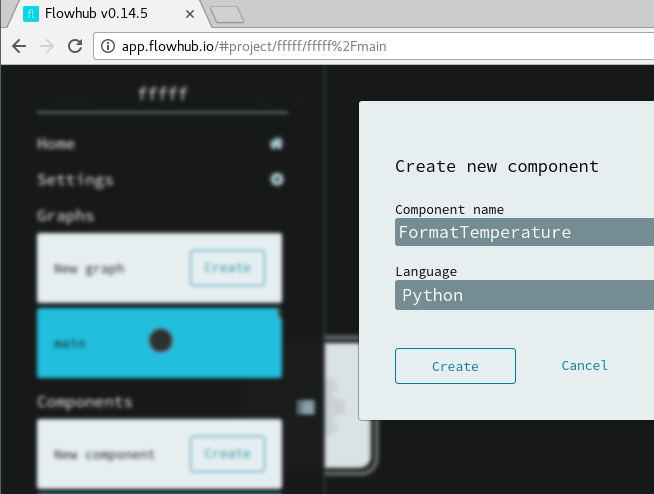

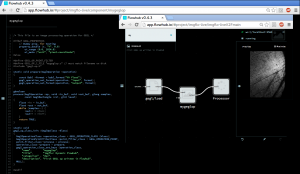

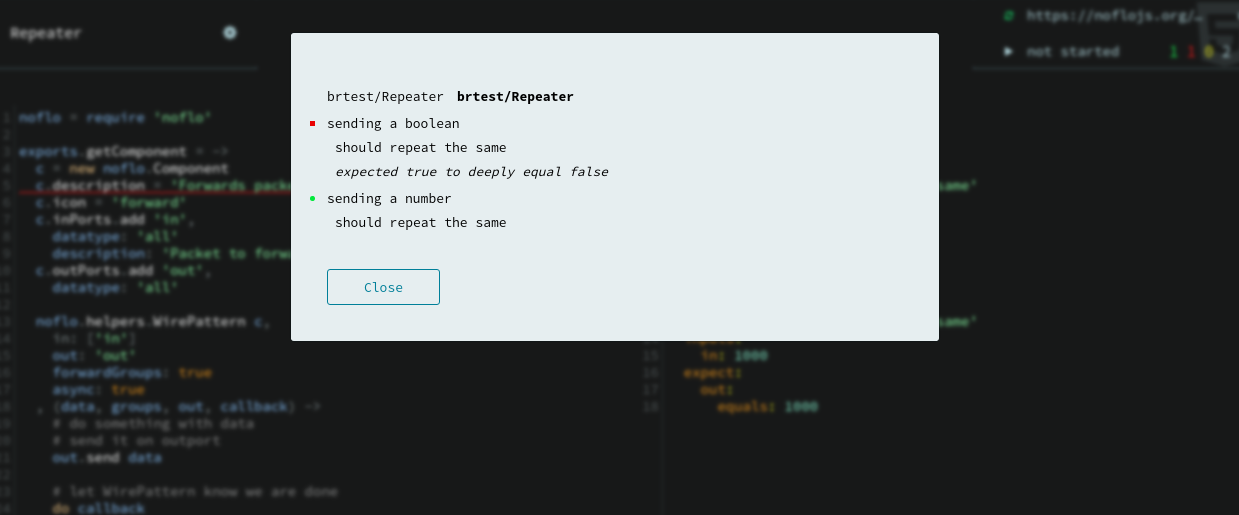

Flowhub integration

The Flowhub IDE is a client-side browser application. For it to actually cause changes in a live program, it communicate using the FBP runtime protocol to the FBP runtime, typically over WebSocket. This standardized protocol is what makes it possible to program such diverse targets, from webservers in Node.js, to image processing in C, sound processing with SuperCollider, bare-metal microcontrollers and distributed systems. And since fbp-spec uses the same protocol to drive tests, we can edit & run tests directly from Flowhub.

This gives Flowhub a basic level of integrated testing support. This is useful right now, and unlocks a number of future features.

On-device testing with MicroFlo

When programming microcontrollers, automated testing is still not as widely used as in web programming, at least outside very advanced or safety-critical industries. I believe this is largely because the tooling is far from as good. Which is why I’m pretty excited about fbp-spec for MicroFlo, since it makes it exactly as easy to write tests that run on microcontrollers as for any other FBP runtime.

Testing microcontroller code using fbp-spec

To summarize, with fbp-spec 0.2 there is an easy way to test FBP components, for any runtime which supports the FBP runtime protocol (and thus anything Flowhub supports). Check the documentation for how to get started.